If you have not seen The Grand Budapest Hotel, go see it now. It is incredibly clever, gorgeous, quirky, and in my opinion Wes Anderson’s best film to date. It is also in my opinion Alexander Desplat’s best score to date, which brings us to our usual question: What makes the score so good? First we will take a look at the setting and the film’s basic premises, and then we will discuss how Desplat reacted to them. Read on…

Welcome to Zubrowka

Since first impressions are always the most powerful ones, let’s take a look at the film’s very beginning. A slide reads:

“On the farthest eastern boundary of the European continent:

The former Republic of

ZUBROWKA

Once the seat of an Empire”

Kind of like the good old “Once upon a time in a land far, far away,” right? Only that “a land far, far away” has a name, and a history of its own. The film quickly introduces us to its namesake, The Grand Budapest Hotel, “a picturesque, elaborate, and once celebrated establishment; I expect some of you will know it.” and its owner Zero Mustafa, who “will no doubt be familiar to the most seasoned persons among you.”

Do you see what Wes Anderson is doing? Right off the bat, the film invites us to this place and wants us to believe in it. Now this isn’t an easy task, is it? Especially when that place looks like this:

And that is perhaps the best thing about the film and its score: It doesn’t take itself too seriously, yet manages to make us suspend our disbelief for the duration of the film, creating a living and breathing place. Our next section will explain how Desplat helps to achieve that, but first: a brief account on nationalism.

Enter Nationalism

There was a world trend in the late 19th and early 20th century for nationalism. Remember all that stuff you studied in high school about a unifying Germany, a unifying Italy, (a little earlier in time) Napoleon, the rise of the Austro-Hungarian empire, etc.? It was sort of a trend, and composers played along. Thirsty with knowledge, music composers sought the original folk music of their lands, aiming to incorporate it into their educated music. I wonder if it is just coincidence that the picture below is from a Hungarian composer – and for those with poor geography knowledge, the capital of Hungary is Budapest.

That is Hungarian composer Béla Bartók, recording peasants singing folk songs. Are you starting to imagine why I brought it up, and what I believe to have been Desplat’s approach?

You Guessed Right: Zubrowkan Nationalism

Yodeling is what starts the film, accompanying the Zubrowka slide. It is an existing piece of music, but nonetheless does the job. You could almost imagine the people above singing it – if you can forgive the fact that they are from two different parts of Europe. The score also features prominently an Eastern European instrument called balalaika, which Desplat marvelously mixes with a symphony orchestra; just as it would have been were this an actual nationalist piece. Balalaikas, mandolins, cimbaloms, they all make the instrumentation of this great score, and they match the region where Zubrowka is technically located.

Enough with the instruments. What about the notes?

It’s all about finding Zubrowka’s sound! You know, because when you are in Japan you hear something like this:

And if you’re in Spain, you hear this:

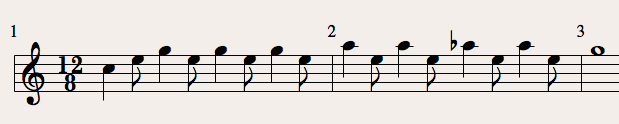

So cliché! Right? Modern western music is mostly built around these two scales:

Those are major and minor scales (also known as Ionian and Eolian), while the Japanese scale above was the Ryo scale…

…and the Spanish one is simply known as the Spanish scale – a Mixolydian b9 b13 with an extra minor third, for the musicians among you.

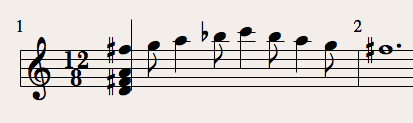

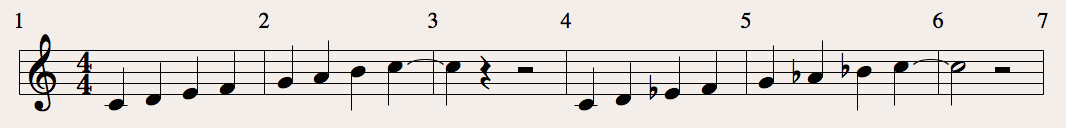

So the idea is that you need different distances between the notes, different intervals. Desplat knows that if he wants to give that impression of a far away land, he needs to break away from traditional Western intervals, and that’s sort of where he is free to explore whatever he pleases – and where it would get really hard for me to prove where he found it without talking to the guy. What matters here is that if you were to hear from Zubrowka later on, the notes would be along these lines:

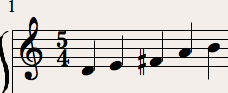

That’s just me improvising on Zubrowkan terms, borrowing from some of his themes. Which I took from here:

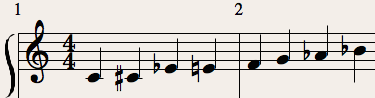

Also here:

And here:

Desplat knows that the idea of foreign is given by mixing in intervals that don’t normally belong in Western Music. I found it hard to find an actual pattern, so I believe he just played around with different modal ideas until he found groups of notes that stood out and turned them into motifs – it would get a little extensive if I wrote about that (including what I meant by “modal”) but perhaps I’ll tackle it in a different post. And it works.

You see the level of detail in Anderson and Desplat’s ruse? With a careful selection of instruments and scales, Alexander Desplat invents a crazy, funny, quirky, impossible-yet-somewhat-real place, just as if he were Béla Bártok (or any other nationalist composer) finding folk music in his land.

There is a lot more that can be said about the score, but this is all we’ll talk about here, since it’s what best matches our approach. It is however enough to make me want to book a one-way trip to Zubrowka and spend a year studying it! Wes Anderson creates this colorful world full of very interesting people and crazy situations, and it’s so fun to live in it that it makes you sad that the film is over. Alexander Desplat did the same, and you just learned how.