John Williams and Steven Spielberg know what dreams are made of. The duo that for almost half a century brought us dozens of eternal classics, have teamed up once again to add their charm to Roald Dahl’s story. The magic of films like Close Encounters, E.T., and Hook, is present in The BFG, a film about a friendly giant who catches dreams to keep us (humans) dreaming. The film captures the innocence, excitement and love of Roald Dahl’s story with the help of one of my favorite John Williams’ soundtracks in recent years. What is it that makes the score sound this way? My analysis below.

Big Friendly Giant

The BFG tells us the story of Sophie (played by a remarkably talented newcomer called Ruby Barnhill), an orphan girl who lives in an orphanage in London. One night, Sophie is visited by a Big Friendly Giant (BFG) who takes her to Giant Country. Unlike other giants, the BFG does not eat humans, and instead protects Sophie from other giants when they try to eat her. With the help of John Williams’ dreamy score and Barnhill’s tasteful acting – her mature versatility and expressiveness makes it hard to believe we are looking at a 12-year old girl – along Mark Rylance’s charming motion-captured performance, it’s hard not to love with the story and its setting.

Sophie and the giant

If there is one thing that sets John Williams’ scores apart from many others, is the inventiveness and singability of his themes. It’s common to watch a film scored by Williams and find oneself singing a theme or two after the credits roll. Additionally, as it’s been pointed out in some of my previous posts, his scores tend to use leitmotifs representing different characters and elements. The BFG is no exception, inviting us to dream in Giant Country with the help of a wonderful score.

Dream Fabric

So what is it about the BFG’s score that is so inviting to dream? First of all, the choice of instruments. Think of musical instruments as air-moving machines – which is what they are. The lower and bigger these sounds are, the more air they move, making them seem more concrete and mundane. Imagine a big, loud horn played next to a table full of utensils. What do you think would happen? If you imagine the utensils shaking, you are correct. Since they can physically move our concrete world, we tend to perceive low and loud sounds to be more “real.”

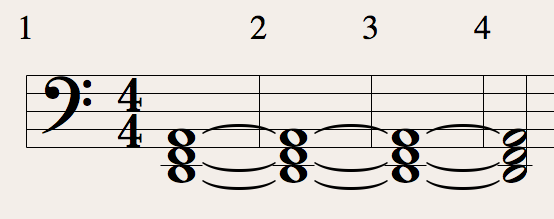

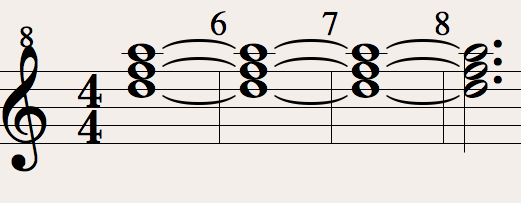

Now imagine the exact opposite: flute and harp arpeggios. If the low sounds of the tuba makes us think of something big, bulky, and mundane, like a ship or train, high-register flute and harp arpeggios do the exact opposite: they make us think of something airy, ethereal. Combine that with colorful chords and you’ll be transported to a world of magic. To illustrate this, here is an uncolorful chord:

What makes this chord uncolorful? First of all, it does not include any embellishments: it is comprised of just a root, a third, and a fifth. Secondly, its notes are low, showing comfort and mundanity. Low notes are commonly used for letting us know that whatever note is being played should be identified as a tonic (think of it as a homebase) and are usually a good clue to know in modern academic music what could be perceived as a tonic or root – it’s a subject of analysis when dissecting post-tonal music. Don’t dwell too much into that, and just listen for yourself: This is the same exact chord as above, but played a few octaves higher:

So what do the flutes and harps play? This, a m13 arpeggio (slowed down for the analysis):

So how does Williams use these elements to convey the magic? In contrast with the Londonian world. Whenever we are not in Giant Country, or when we are not seeing hints of magic around us Williams leaves it up to diegetic sounds to underscore the scene, or uses a score that would be fitting of the diegetic world: royal fanfares when we are in Buckingham Palace, and the sounds of ambulances and the Big Ben when we are in the middle of London.

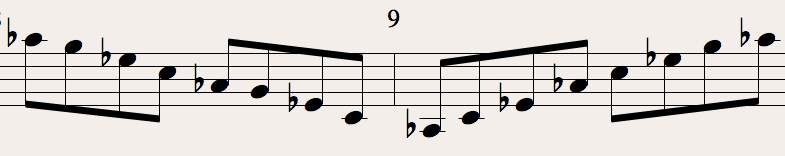

When we are in Giant Country or looking at the BFG, however, Williams uses his magical themes to create mystery, excitement, love, and fear. The mean giants are accompanied by low brass, the adventurous moments by fast strings, and the mystery and fear by this progression:

Recognize it from somewhere? Maybe this other famous John Williams theme:

As the story evolves, our Big Friendly Giant becomes less of an unknown and more of a friend. As friendly love blossoms between him and Sophie, so does the theme that represents their interaction. At first, since Sophie is our link to the BFG and his world, the main theme is presented with wonder and fantasy, but as their relationship evolves (and so does ours), the theme becomes more human and representative of their friendly love. The theme that at first was played by a flute, is now played by an oboe.

Same theme. Different instruments. Williams uses the oboe to give the BFG humanity, the first time when we learn more about him as he tries to explain that, unlike the other giants, he is a good guy who doesn’t want to eat humans. Also, once it’s been established that the BFG is friendly, the theme with low brass and bassoon becomes the other (unfriendly) giants’. Williams’ score’s evolution keeps us dreaming and wondering, just like you would expect of a film about a little girl meeting a fantastic being who brings us dreams.

Your Thoughts

What did you think about the BFG and its score? Did they make you dream or did they make you fall asleep? Do you feel like you can appreciate the soundtrack more after reading this post? Let me know in the comments below!

Note: After originally believing that this blog should not have ads, since I do not use it to profit from ads, I finally decided to add some Amazon. The reason for this is simply to give you the chance to enjoy the soundtracks and films that I analyze, especially since hopefully you will feel more prepared to enjoy them after reading my posts.