[Note: As this article was being prepared to be published, we tragically lost one of our greatest composers, James Horner, to a fatal plane crash. You may expect a post from me about Mr. Horner soon, and you may find out more about the content and frequency of my blog posts here.]

When faced with limited resources, most composers will either reject a project or take on monumental tasks that, due to the unavailability of such resources (read: time and money) will end up in trouble for parties involved…

This should be enough to hire an orchestra, right?

But don’t worry! There are alternatives.

I would like to start by making clear that, according to the director of The Living, Jack Bryan, the reasons why he chose to have a shorter soundtrack with fewer instruments were purely aesthetic and had nothing to time or budgetary restrictions. This is noticeable in The Living, but it nonetheless provides us with a good strategy for scoring a film if the resources were indeed limited. Read on…

Enter The Micro Soundtrack

When Writer/Director Jack Bryan started searching for a composer for his feature film The Living, he wanted to keep things natural. The Living has a very real and visceral way of presenting things – particularly death and life – and having a soundtrack with a lot of non-diegetic music would have probably distracted the director from his intentions of keeping things this way.

Now don’t get me wrong, there wasn’t much of an alternative for a composer here: The director wanted a short score. This was not up to the composer to decide. But does that mean that such score is not an option for times when resources are not abundant? Could we possibly learn a valuable lesson from The Living, on how to write a short score? Let’s see how they did it.

A Riveting Thriller

From The Living‘s Press Release:

“Awakening from an alcohol induced black out, Teddy (Fran Kranz) discovers he has severely beaten his wife, Molly (Jocelin Donahue). As he seeks her forgiveness, she struggles with a possible future together. Absent a father’s protection, her brother’s humiliation over not being able to defend his sister quickly turns to hate. In desperation, Gordon (Kenny Wormald) seeks out and hires an ex-con (Chris Mulkey) to kill Teddy setting forth an unstoppable sequence of shocking events. Redemption, revenge, forgiveness, inhumanity interweave in an ill-fated tale of life and unforeseen circumstances.”

As the film starts, images from rural Pennsylvania fill the frame accompanied by a song titled The Werewolf, by Michael Hurley, about an animal (or individual) that acts menacingly at night and regrets its decisions afterwards. And while in this case the lyrics match with the story the film is telling, there is a beautifully disturbing marriage of a soothing melody and a darker lyric that does a great job at setting the tone of the film. We feel lonely, blue, and a bit threatened, as well as intrigued to find out more. And in regards to the purpose of this post, the intimacy of a pastoral chant accompanied by an acoustic guitar can give us a clue about what could work regarding instrumentation.

Much alike this song, although on a different scale, the De Luca brothers – composers in charge of the film’s original score – rely solely on string instruments. There is something delicate and lonely about strings that works really well in this film. Think of Gustavo Santaolalla’s scores (Brokeback Mountain, 21 Grams, Babel), and you’ll realize that this approach can be very effective – and in his case, accompanied by an immense amount of talent, win two Oscars in a row.

Now of course, this was perhaps the predictable part of this article. Few instruments mean lower costs in writing, arranging, and performing, so that seems like an obvious decision for a low-budget soundtrack – and I repeat, this was not at all a motivator for The Living. But it is really all about picking the right instruments! More particularly, it is about choosing the ones that make your story breathe.

What To Score

I have not written much about this in the past – probably because there is a lot said about the subject and really little for me to add to the table – but as you may have read on my previous posts, there are different approaches on what music can do for a film. As a composer you have a big role in what an audience will come to expect of the story: for example, if you choose a motif to underscore every time a character is thinking about killing someone, but then during one scene there is no music behind the character thinking, then the audience will believe that he is not thinking about murdering that someone in this particular scene. The reason I bring this up is simple: if you choose a strategy, you have to stick with it – and if you plan on writing less than 10 minutes of music for an entire feature, you better choose a very focused strategy.

In The Living, Director Jack Bryan and the De Luca brothers chose to use music to express characters emotions. There is music when Gordon is nervous about facing Teddy (his sister Molly’s abusive boyfriend), music when Molly is struggling about her decision to stay with Teddy or not, and music again when Gordon decides (while having second thoughts) to call the hitman to “take care” of Teddy. This music, underscoring Teddy’s nervousness and inexperience in this matter (which he will hopefully share with the audience, something very helpful when telling a story) accompanies him through the film’s initial turning point, kickstarting the second act. But we can’t really say that’s a strategy: it’s just a role. So what if we chose just certain emotions? Better yet, what if we picked very specific points of the movie to do this?

It’s All About Form

You are probably already guessing where I am going with all this, and it all comes down to one little fact: how to tell a story. Whether we are watching a film or listening to a symphony, we enjoy having some sort of clue of where we are. Music connoisseurs know sonata form, and smile when the original theme returns. Filmgoers said to themselves “What on Earth is going on? I thought this movie was over!” when the T-rex got loose in the city at the end of Jurassic Park II: The Lost World. We like to know where we are in a film, story, or speech, because it helps our brain categorize the information that we are processing and understand it better.

I’ve said this many times in previous posts, and I’ll keep saying it: film composers are dramatists. We are here to tell stories. So paying attention to the film’s structure is utterly important. And this approach may not be purely intentional in The Living, but it is at least in some way. If Jack Bryan is the great storyteller that he seems to be, he has already embraced all this, and his characters are having their most important second thoughts during key points of the film. These are the points when the original score comes along.

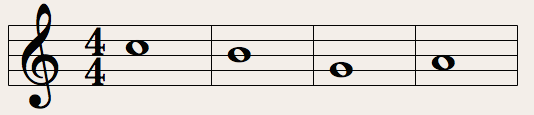

With just a four-note motif and a few developments of such theme – tending to be longer and more static than in its original form – the film gains its full palette to apply precise brushstrokes that express characters’ emotions during specific plot points. Here is the theme in its fuller form, abbreviated and played over triads – those familiar with my blog posts will know that I play everything on the piano in order to abstract theme development from orchestration, something that often gives non-musicians some struggle.

From those four notes, the composers will grab one or two, stretch them out, play with the harmony just a bit, and rely on lonely plucked and bowed strings to accompany. That’s it. It works, and it fits the film. And everyone is happy.

But… Will It Work For Me?

Perhaps! I could write forever about examples of films where this would and wouldn’t work, but then again… you could prove me wrong! Understanding the score’s purpose in the overall scheme of things helps a lot, and this score is an example of one way to do it. This is not a manual of how to score any feature film with just a few minutes of music, but rather a way of showing you how it can be done.

Also, don’t forget that film is a collaborative art. If you try to make a great film out of a mediocre script, you’ll end up with a mediocre film. If an actor delivers the performance of a lifetime but you can’t understand the dialog, then that performance is as good as the quality of the recording. Your score can be as great as it will ever be… but do you think that if the rest of the film sounds awful, your score will be any good? The Living has a great balance of diegetic sound and a non-diegetic score, working well in the film’s favor. There is a nice balance in things for the most part, and the fact that there is a good soundtrack overall (in reference to sound effects) does make things a whole lot better for the De Luca brothers’ score. We feel like we are (according to Bryan) “nakedly in the moment” when brutal and tense scenes take place, and the film’s prevalence of just visceral diegetic sounds help to keep things real.

I’m not gonna tell you that this will work every time, and also you will be restricted by what the directors and producers need. But what if you could convince them? If they understand their restrictions and are willing to work around them, why not try it? As you can see, there are ways to make it work.

If you missed the link above, you may find The Living available On Demand here.